An Intimate Interview with Iconographer & Poet

Ptahmassu Nofra-Uaa

We live in an Aristotelian world; a descriptive mindset where essence is subordinate to parameters by which we describe it, a world that denies its own soul and metaphysical nature and pretends to find its identity in a labyrinth of systems which insist on presenting us with the walls that constrain and limit our senses as a guide towards an exit, yet only promote the part over the whole. Plato is loved by most, revered by almost everybody, yet hardly understood. We have replaced our own consciousness, the very belief in our communal soul, with the limited perspective of totalitarian materialism. Even those who believe in the primacy of ideas find it hard to experience such ideas: we use them, we describe them, we categorise them and dissect them, but do we feel them? We think of ourselves as superior to our antecedents, yet not so long ago, Humans had a dimension we have now lost, a transcendental dimension that allowed us to appreciate, not just analyse, symbols. When Professor Gombrich, in Art and Illusion talks about the Medieval mindset as preferring the symbolic over the representational, we hardly understand that he is pointing to this very dimension of our nature that allows us to be part of the whole, part and the whole, not just part.

I was immediately interested in Ptahmassu Nofra-Uaa’s work on encountering his magnificent icons: I started wondering why an artist would, in a world where the illusion of description has replaced reality, where realism has a tyrannical hold on our minds, ride against the tide and dedicate his work to a form of art which is so often misunderstood, so often misinterpreted as ‘incorrect representation’. The irony and hubris of this concept! An icon does not intend to represent, but to be a symbol, a link between the relative (to which we have now sold our souls) and the universal, between the limited and the limitless. We have, since first meeting, found that we have many beliefs in common, not last our search for a renaissance of the symbolic, of the transcendental.

This search is as present in his visual Art as in his Poetry, where symbols and emotions merge, in an expressive torus where the personal becomes universal, where the fragmentary, individual experience, becomes whole in a perfect marriage between emotions and symbols. I am therefore extremely honoured to present this interview with a great Artist: Ptahmassu Nofra-Uaa.

Adriano Bulla

What made you undertake the journey to becoming an iconographer? And why did you choose icons as a way of expressing yourself?

Ptahmassu Nofra-Uaa

Where to begin? I guess you could say that iconography has always been in my blood, that I was born to it. Strangely enough, I was born into a very conservative Christian family, Baptists, so in these regards one might wonder where my love of icons came from. Baptists don't use icons or images in their observation of Christianity, unlike Catholics or followers of Greek and Russian Orthodoxy. But my father was a painter, a watercolourist and oil painter who specialized in landscapes and nudes. He also had a strong connection with traditional Biblical imagery, and in particular scenes of the Passion and crucifixion of Christ.

What made you undertake the journey to becoming an iconographer? And why did you choose icons as a way of expressing yourself?

Ptahmassu Nofra-Uaa

Where to begin? I guess you could say that iconography has always been in my blood, that I was born to it. Strangely enough, I was born into a very conservative Christian family, Baptists, so in these regards one might wonder where my love of icons came from. Baptists don't use icons or images in their observation of Christianity, unlike Catholics or followers of Greek and Russian Orthodoxy. But my father was a painter, a watercolourist and oil painter who specialized in landscapes and nudes. He also had a strong connection with traditional Biblical imagery, and in particular scenes of the Passion and crucifixion of Christ.

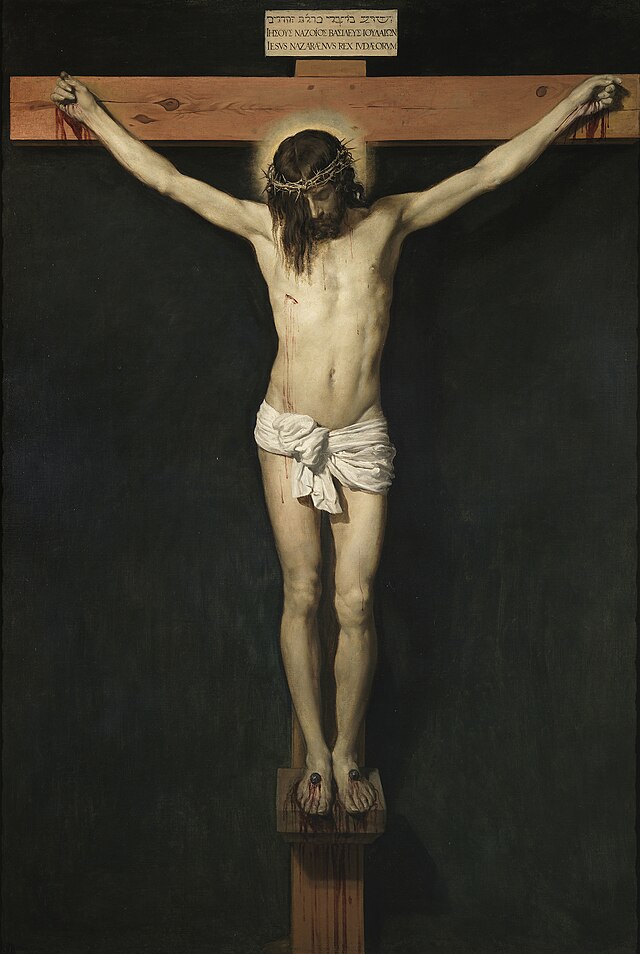

I remember the first time I saw a painting of the crucifixion and the effect it had on me, even as a very young child. Here was this practically naked man, bleeding and brutalized, whose eyes were rolling up to heaven. It's an image of innate death and violence, and yet I recognized that it was a symbol for a deeper mystery. It was about death and blood becoming the seeds of redemption and resurrection...immortality. I saw something in this image that challenged the very idea that death as a finality existed at all. This idea of immortality, resurrection became an obsession for me. I guess it opened up the doorway for an inquiry into mysticism.

|

| Cristo crucificado by Diego Velázquez, 1632. This image was in the front of the family Bible my parents kept on a stand in our living room. It was the first iconic image I became obsessed with as a young boy. |

So, when I was still a boy...oh, about six years old or so...I discovered the religious art of the ancient Egyptians in one of my father's books. He was a student of anthropology specializing in ancient Mediterranean cultures, so the bookshelves in his den were filled to capacity with volumes on ancient Near Eastern civilizations...art, religion, mythology...the Greeks, Romans, Mesopotamians and Egyptians. But it was the Egyptians who captured me, because of their invention of mummification and belief in an afterlife, which seemed to dominate their whole culture. I mean, there was this entire funerary industry that fueled the Egyptian economy, and it existed because the Egyptians appeared to know that this one lifetime was not all there was...that immortality was an assured aspect of the cycle of life and physical death.

But as an answer to physical death, the Egyptians perfected the art of mummification, which I think was what first drove me to become obsessed with ancient Egyptian history and religion. Mummies and the mummification process became the first truly obsessive areas of study I engaged in at the time I began to take reading really seriously.

My father took my younger brother and I to the Museum of Man in Balboa Park (San Diego), which at that time had a very small collection of Egyptian antiquities. But front and centre in that collection were two mummies...one from the Third Intermediate Period, I think, and the other from the Ptolemaic dynasty. The one I think was from the Third Intermediate Period (maybe a little later than that) still had ornamentation on the outside wrappings, funerary images on cartonage (linen and plaster). These had a large impact on my mind. I knew that these figures of deities were magically charged by the Egyptian priests, that rituals had been performed on them at the time of the funeral rites. To the ancient Egyptians, these were living images, living deities whose very presence on the mummy's wrappings were part of the technology of achieving immortality.

I recall going back to the Museum of Man throughout my childhood and young adult life, going back specifically to spend countless hours just sitting in front of those two mummies...tuning in to them, as I described it to my father at the time, connecting to what I felt was a living spiritual presence still dwelling near those ancient Egyptians. For me, the fact that those mummies existed at all was proof positive that the Egyptians had discovered immortality...that they were in possession of a spiritual technology that we had yet to understand or uncover. Underneath all of this was a conviction I had that it was the physical images, the statues, mummies and hieroglyphs, that held the potency of the Egyptian religion. I always looked at the religion of the Egyptians as something very much alive...not as a pagan, idolatrous or dead religion...but as a living force that could still be accessed in the present day and age. Of course, it goes without saying that I still believe this very much today!

I began to pray to Egyptian deities when I was just six years old. Of course, I never told my parents about that! They assumed that my enthusiasm, my obsession with Egyptian mummies and religion was just part of a childhood fascination with ancient Egypt and Egyptology. My father encouraged this because of his focus on anthropology and archaeology, but also, in part, because of his studies in Egyptian art and architecture. He had plenty of reading and visual resources for me, so I devoured these voraciously. But underneath my outward interest in the formal, academic study of ancient Egypt was always a very strong undercurrent that some might call metaphysical, but for me has always been the conviction that the gods of ancient Egypt are living gods, and that the religion of the ancient Egyptians is as valid as any of the mainstream religions of the current era.

My father began to teach my younger brother and I how to draw and paint practically as soon as we learned the alphabet, and part of our artistic education was learning how to copy the work of other artists...the Old Masters and the like...but also the works of ancient artisans, so of course I chose the ancient Egyptians. I would spend hours on a lot of days copying tomb and temple scenes of Egyptian kings and deities, working on perfecting my hieroglyphic hand and getting the details as precise as possible. My father would give me "assignments"...pictures of things to copy, and I had to copy and re-copy until he felt I had learned my lesson.

My father would never have looked at these exercises as the practice of iconography. I'm sure that in his mind the only legitimate expression of iconography was Christian iconography, which was the visual expression of the only belief he believed was valid. My current experience is that a lot of people who first encounter my work think of it in terms of Egyptology art, or art somehow paying homage to ancient Egyptian mythology. People today don't see Egyptian religious images from the vantage of faith or belief or an active religion, but rather as figments of a dead civilization...a pagan religion or mythology.

These are points of view completely alien to me! I don't think in such terms...looking at any sacred or religious image, past or present, and thinking oh, that's mythology (as in fantasy, fictitious imagination), that's the product of a dead religion, a false religion. No matter what tradition a religious image is coming from, I experience all religious iconography as part of the Mysteries or initiatic experiences of a particular people's spiritual way of life. I don't discount the images people have invested their faith in, even if those images don't belong to my religion. As an iconographer I have the utmost respect for all sacred images...images of faith...because they are works ultimately connected to the Sacred, the Divine, Deity...whichever name is being assigned to it.

I can't look at my life as an artist and say there was one specific moment where the cosmic light bulb clicked on...where I said to myself I want to be an iconographer. I think the idea was planted in my childhood and simply grew. When I was copying Egyptian temple and tomb scenes, I don't think I consciously had this idea of painting sacred images for use in worship, as I very consciously do now. I always had this feeling that these gods wanted to come through into our world, that they were living on the other side of a curtain...with them on one side and humanity on the other. It was through images, statues and hieroglyphs, and even mummies, that the gods could have access to our world, and we to theirs. That was always an idea floating around in the back of my head, and somehow I realized that in copying the ancient religious images of Egypt that I was giving the gods a hand in making their way over into our world.

I think I finally just answered the second part of your question...why did I choose icons as a way of expressing myself? The easiest answer is, for me, the most obvious one...because humankind is in a reciprocal, interdependent relationship with the Gods, and it is through the action of creating sacred images that the Gods and humankind come together, to a meeting place, to a focal point where the adorer and the adored exchange a dialogue. Somewhere along the line in the practice of my religious convictions I felt compelled to merge my artistic impulse and my spiritual beliefs into a single machine.

I'm what you would call a Kemetic Reconstructionist. There are many different ideas out there concerning what Kemetic Reconstructionism is or isn't, so I'm in no way slapping an authoritative label on it on behalf of others. My way of experiencing Kemetic Reconstructionism is that it is a tool for reviving the ancient Egyptian or Kemetic spiritual traditions and practices, using the work of academic Egyptologists...scholars, specialists in Egyptian religious texts, and members of the wider archaeological community...and by using these resources as our foundation or reference point, we can, as much as is possible, connect with the living deities of the Egyptian religion as the Egyptians themselves did. There are, of course, a lot of grey areas or missing threads that we just can't put back in without a certain amount of guesswork, and that is why it is vital, at least for me, to have a personal relationship with the netjeru, the gods, via ritual or cultic acts...making offerings, reciting the daily prayers, meditating on deity images.

|

| The shrine to the Household Gods in the front room of my house, the sacred space reserved for the celebration of the Divine Cult in the Kemetic tradition. |

So, this idea of deity images, what academics call cult images, is very central to my own personal connection with Kemeticism as a living religious, spiritual tradition. The use of sacred images or cult statues is very well documented by academics and Egyptologists. We know that the Egyptians were communing with their gods through two and three dimensional works that they experienced as magically alive, charged, powerful. It goes without saying, then, that if you are a person living today who is attempting to connect on that same energetic level with those very same gods, that you would utilize the very same kind of images as your means of touching base with the netjeru...making contact, as it were.

In these regards, the icons that I paint are not about self-expression...they aren't modern art...not in the sense of a contemporary artist using their art as a vehicle for describing their reaction to their life, to the world as it is. Modern art is very involved with the artist as a personal statement reflecting how the individual artist is viewing their surroundings, their human experiences, and then transmitting these to the viewer using a visual language or cues. Modern art has the artist at its centre, and we feel that art must document our current reality in order to be relevant or significant.

However, an icon, a true icon, has a completely different aim in mind. An icon does not give us a window onto our world, our personal tastes, our ego. An icon is a window into a very different kind of world...oh...the world beneath the surface, the world inhabited by our intuition, that there is something much more out there than the mere physical, the scientifically quantifiable. That is just one, more simple way of looking at how an icon functions. But what any icon really does is allows the viewer to directly touch something that seems invisible within other areas of their life. A person may believe in a deity or specific tradition, pray, attend religious services, but it is when we have that intimate brush with a deity that all those other experiences come together to bolster our faith. That is what the best icons do for us. They give a face to the Sacred, allow us to meet the Sacred head-on with our two eyes. Of course, the masterpieces of iconography do even more than that. A truly masterful icon touches a chord so deep inside us that it changes our perception, and remains with us long after we have left the presence of the physical icon.

Now, of course, I've been talking about icons from a more Western perspective here, because the Western tradition of icons is something quite different from the Kemetic, Egyptian and ancient Near Eastern concept of the cult image, which is what I consider my work to be. The Kemetic or ancient Egyptian view of a sacred image is that it is a thing in which a portion of the deity's actual power or spiritual essence is invited to take up residence. The cult image, after being ritually awakened or animated, becomes the focal point for the temple cult...for all of the prayers and ritual actions that draw out the actual power of the deity so that the work of creation can continue. A Kemetic cult image is part of the netjer's, the deity's anatomy, not just a symbol or an inanimate object standing in the place of a concept of deity. The Egyptians were in do doubt that their sacred images were part of the living presence of living gods, and these gods were as much resident in their earthly images as they were in the more invisible world surrounding humankind.

|

| A Kar-Shrine or Naos in which is kept a ritually awakened icon of the God Ptah, the focus of a contemporary Kemetic temple of Ptah |

My icons serve this same purpose. They are ritually activated, spiritually charged images of living gods, and they themselves, that is, my icons, are living gods. Their intended setting is the modern temple or shrine, where they will become the beneficiaries of an active cult...ritual offerings and service to the deity. So, we can't really say that my icons are a way for me to express myself, not in the same way that other "modern" artists do. One can't really say that my icons have something to say about me as an individual, that they are a visual expression of my personal life, my personality; other than the fact that these images are obviously made by an artist who has a connection with the subjects he is painting. That hopefully will come through to my viewers, that these images are the product of true love and devotion, of living service to the Gods. Hopefully that is self-evident.

Adriano Bulla

Some people may regard icons as belonging to the past; how do you think icons can relate to, or even enrich, the modern world?

Ptahmassu Nofra-Uaa

The first thing that comes to mind is an experience I had in June of 2000, when the Office of Tibet invited me to participate in a blessing ceremony the Dalai Lama would be leading as part of an initiative to promote non-violence within the inner city youth community of Los Angeles. A special intimate morning with His Holiness the Dalai Lama, hosted by actress Sharon Stone, had been arranged in the Hollywood Hills, which I attended as part of this larger project. The entire Shi-Tro Mandala for Universal Peace project was being initiated around a single sacred object, a three-dimensional Tibetan mandala that was scheduled to travel to different communities throughout the United States, which would benefit the initiative for non-violence. The hope was that spiritual tools such as meditation could be promoted within communities where at-risk youth were prevalent, that the Shi-Tro Mandala would itself be a springboard for social awareness of the importance of developing mental and emotional peace...also to address the issues of domestic violence and anger management.

During this event, before His Holiness actually blessed the Mandala, he gave a very animated talk about the importance of mindfulness and how changing our perspective, changing our attitude was the first step towards the development of inner peace. That was one reason why, from his perspective, things like Mandalas could be instrumental, because they were training tools for the mind. They had the ability to gather our mental focus and lock it in place, so that we could start doing the necessary internal "legwork" for sharpening our mind. At one point he began discussing the actual construction of the Shi-Tro Mandala, and affirmed that from his point of view such spiritual objects could actually put an imprint on one's karma, basically planting seeds for awareness that could ripen in the future. There was this idea that just by setting eyes on the Shi-Tro Mandala, one could generate a blessing whose effects could be seen not only in this life, but in future lives as well.

|

| The Shi-tro Mandala is the most intricately detailed three-dimensional Tibetan Mandala ever constructed outside of India and Asia. |

This touches on your question...how can icons relate to, even enrich, the modern world. A Tibetan mandala may not be an icon from the Western perspective of what an icon should be, however, I feel that my experience with the Shi-Tro Mandala that morning held up a powerful example for me as an iconographer of the way in which sacred or spiritual images can be used to impact lives in the material world. I mean, here I was, in the Hollywood Hills, in the centre of what some people might say is the Mecca of materialism and greed, and yet I saw this very ancient meditation form, this three-dimensional Tibetan Buddhist mandala, and the effect it had on those who came into contact with it. They had invited a group of inner city youths, some who had been in prison, and gave them the opportunity to share their stories and to view the mandala. You could see that being in the presence of the Dalai Lama made a certain impression on them, but also seeing this amazing spiritual structure, this large Tibetan shrine housing the Shi-Tro Mandala. You could feel a very tangible energetic exchange between these young people and the mandala. It definitely made an impression on them, and one can hope that it triggered some kind of desire to move towards inner peace, spiritual clarity.

That really is my answer to this question, that icons or similar sacred images can touch the mind and change one's perspective. An icon, by using strong symbols, the language of symbols, can elicit a positive and constructive response, or trigger an emotional reaction that awakens things that have been buried deep in the subconscious. Because of such an experience, a person may be able to come to terms with things inside them that need release or relief. Icons work on a different level than our commonplace, everyday stimuli, from my perspective as a painter of icons. They represent the invisible world, the world of faith, which for most people means a certain amount of hope or certainty. Catholics see the crucifix and are immediately reminded of the sacrifice their faith tells them was given on their behalf. This gives them a feeling of hope or strength, and when we feel hope and strength in our convictions, then we feel that there is a way to move ahead, to change or grow or improve our human condition. In my view, this is what icons do for us. They work deep down inside us, in our psyches, touching us in a very personal way, using our relationship with symbols as a catalyst for touching our faith, the Sacred, in the most immediate way possible.

No comments:

Post a Comment